Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club Band

A book I had considered reviewing for the site was Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 by the late historian Tony Judt. Judt’s book is easily the go-to guide to the subject if ever you were curious, though it clocks in at 830 pages. But do you know what caught my attention more than anything? The cover.

Take a look.

Can you spot what’s unusual? I’ll spoil it for you, it’s the Beatles. Though the band received scant mention in the book itself, I am always blown away by the fact that the Beatles, and only the Beatles, make it into a general history book. How was it that John, Paul, George and Ringo found themselves sharing cover space with Berliners tearing down the wall?

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a massive Beatles fan. They’re a band that few if any people dislike. Younger generations may not go apeshit when hearing their music the way the Boomers did, but we’re not fools—these guys are second to none.

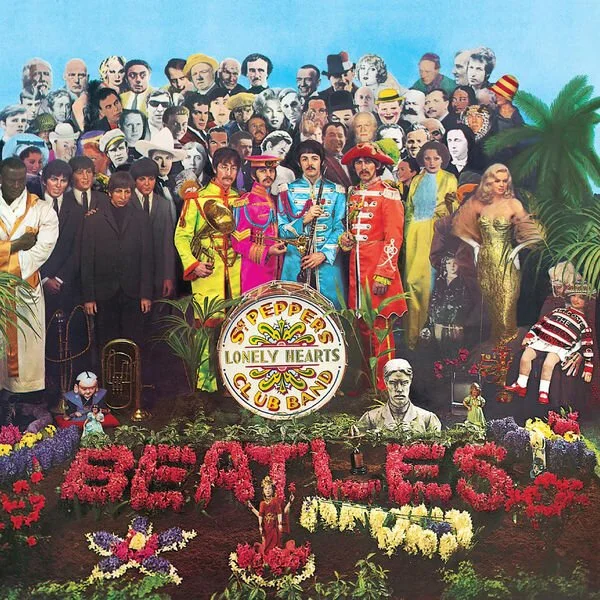

So, I’m gonna talk about the most famous Beatles record, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

The Beatles Again.

By November 1966, when Pepper’s recording sessions began, the Beatles were at war with their fame. From 1963 on, an entire generation of teenage girls screamed, pissed themselves, and fainted upon seeing them. The band had to crank out a breathtaking two albums (14 songs each) and two singles a year when they weren’t constantly touring or else filming movies.

By 1966, the Beatles were becoming more interested in their recording studio, the now famous Abbey Road. The studio was a safe haven from the barrage of fans who constantly hounded them outside the walls, and Abbey Road’s technical potential had yet to be unleashed in their music. Of course, the substances the band were indulging in informed their musical tastes as well.

It was these separate elements that contributed to Pepper’s predecessor, the much-loved Revolver. Songs like Eleanor Rigby, Yellow Submarine, and Tomorrow Never Knows tower over popular music even to this day.

But the gap between Revolver and Pepper really was something else. The literal gap (Revolver was released on August 5th 1966, and Pepper seemed to take a then-ungodly ten months to appear on June 1st, 1967) matched the metaphorical gap. The old mop-top Beatles were truly dead (and taxidermied on the cover of Pepper). The music that emerged had a sophistication that the straightforward collection of tunes on Revolver couldn’t match.

The Pepper sessions began with, ironically enough, a song that didn’t make the cut for the record—it was deemed too good and so released as a single. That song would be Strawberry Fields Forever, John Lennon’s psychedelic ode to a Salvation Army Home in Liverpool. Its four-and-half minutes featured everything and the kitchen sink including a swarmandal, an orchestra section, backwards cymbals, the world-famous flute intro played on the Mellotron and one allegedly hidden message. It is the greatest tribute to one’s hometown ever made…with one exception.

Lennon’s songwriting partner Paul McCartney had penned his own tribute to their hometown. McCartney’s piece was Penny Lane, the name of a street in Liverpool which is now a massive tourist attraction. The street signs reportedly had to be nailed to the buildings because fans kept stealing them. The song Penny Lane isn’t as complex as Strawberry Fields Forever but it certainly features a full contribution from the band as well as a slick trumpet part played by David Mason.

Both songs were released as a single in early ‘67. In those days, singles were never included on albums because that would be “conning the public”, in the words of producer George Martin. He claimed releasing those songs as a single was the biggest mistake he ever made—and do you know what? I totally believe him.

In short, Sgt. Pepper, named by Rolling Stone as the greatest album ever made, was released without its two best songs on it.

I’ll let that sink in.

The Album Proper.

The album begins with the sound of a pit orchestra warming up and an audience getting settled—sound effects culled from Abbey Road’s extensive recording library. Then Ringo Starr crashes into the opening of the title track on his drum kit. The crunchy rhythm guitars soon give way to a wailing lead guitar part supplied by George Harrison. The Master of Ceremonies, McCartney, introduces the band (“the act you’ve known for all these years”) before a special French Horn quartet comes in to entertain the crowd. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison welcome the audience into the show with the backing chorus while Starr and the horns keep them moving.

Harrison’s fiery guitar returns over McCartney’s bellowing introduction of “the one and only Billy Shears”. The horns fade and a loud sample of a screaming crowd erupts into a musical segue, leading the band to announce the arrival of “Billy Shears.” Billy Shears a.k.a. Ringo then steps forward to sing his song, With A Little Help From My Friends.

The recording of With A Little Help From My Friends was a mostly straightforward affair once the musical segue had been achieved. Starr, never having been much of a songwriter, relied on Lennon and McCartney to write him a tune for this album, which they duly procrastinated on. Eventually, when the finished lyrics were presented to Starr, he had a complaint. Originally, the lyrics said “what would you think if I sang out of tune/would stand up and throw ripe tomatoes at me?” Starr loathed that lyric and wagered (probably correctly) that were he to sing it, he would be dodging tomatoes for the rest of his life. It was hastily amended to “would you stand up and walk out on me.”

Starr reportedly had other problems, not with the lyrics but with his singing. Starr has, by his own admission, never been a confident singer. For the final bellowing note, “…with a little help from my ffffrrriiieeeenddssssss!!!”, it took McCartney, Lennon, and Harrison cornering him into the vocal booth until he did it.

With the first two songs joined as one via a crossfade, the stoned Boomer audience of ‘67 believed that the Beatles, under their Sgt. Pepper guise, had created a “concept album”—something totally new. Lennon disagreed in later years, citing his next offering as proof that the songs “could have gone on any other album”.

Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds is a committed group effort led by Lennon. The lysergic Lowery organ notes at the beginning, alongside Lennon’s heavily tape-altered voice, helped paint the background for the most colourful lyrics ever committed to a sound recording. It’s easy imagining Lewis Carroll nominating the song as Wonderland’s national anthem. Speaking of Wonderland, some thought Lennon took a detour to that location when searching for the lyrics.

In addition to flanging effects on just about every instrument and vocal track, the nouns in Lennon’s title had the curious initials LSD, the very name of the substance which he consumed on a regular basis. The inspiration seemed obvious, but the band firmly rejected this druggy interpretation. Right up until his death, Lennon maintained the lyrics referred to a painting his four-year-old son Julian created in school of a classmate named Lucy. (Such a girl did indeed exist and so does the painting.) Still, nobody who listens to the song could reasonably claim that LSD didn’t going into the making of L.S.D.

Afterwards we go from the ultimate acid trip song to the ultimate song about self-improvement, Getting Better. McCartney, with a little help from Lennon, was the primary composer of this straightforward rocker about a reformed douchebag. The narrators cheerfully describes his old life as an “angry young man” who “used to be cruel to my woman/I beat her and kept her apart from the things that she loves”. The disarming verses are juxtaposed with Harrison and Lennon supplying chipper guitar licks and happy-go-lucky backing vocals. On top of the rhythm track, Harrison threw in a tambura while Starr added congas.

In a glorious twist, the song about self-improvement was lost on Lennon during the recording of the backing vocals. Lennon, who often brought pillboxes into the studio to keep him awake, accidentally took a different pill—LSD (I think there’s a theme here). After a few recording takes, Lennon complained of feeling unwell to producer George Martin, blissfully unaware of the band’s chemical diet. Martin, in a feat of remarkable innocence, took Lennon up to the roof for some fresh air lest he be attacked by the swarm of fans keeping a constant vigil outside the studio gates.

When McCartney and Harrison inquired as to the whereabouts their AWOL bandmate, Martin’s description somehow alerted the other Beatles to what Lennon did. They made a mad dash up the stairs to the roof before Lennon accidentally committed the dumbest suicide in history.

Getting Better is followed by the claustrophobic-sounding Fixing A Hole. Unusually, Fixing A Hole was not recorded at Abbey Road, but instead in a rubbish studio called Regent Sound. Fixing A Hole features McCartney playing harpsichord on an airless recording while Lennon, taking up bass duty, and Starr fight to have the song’s low-end be heard over the terrible acoustics. Only Harrison’s underrated lead guitar lines can be heard over McCartney’s whimsical lyrics about who knows what. Some thought Fixing A Hole was about heroin (which McCartney denied). Rather, McCartney seems to be talking about the “mind wandering” of creativity. Fixing A Hole helps anchor Pepper in place, but adds little in terms of innovation.

The same could not be said for the next track, She’s Leaving Home. This track was heralded as the standout on Pepper’s release. Though it has faded a bit over the years, the maturity of the storytelling in the song’s three and a half minutes is still mind-blowing. McCartney sings of a girl who runs away from home (a common occurrence in 1967, as wayward youths made their way to Haight-Ashbury). Yet rather than follow the girl on her adventure, McCartney, with more help from Lennon on the Greek chorus, instead focuses on the parents who struggled to comprehend why she ran away. Lennon and McCartney’s portrayal of the parents is sympathetic, a feeling backed up by the string nonet—and no other instruments. McCartney asked freelance arranger Mike Leander to compose the beautiful score due to George Martin’s busy schedule. Martin conducted the orchestra, although he felt slighted by McCartney going with another composer at the time.

There’s another heart-warming twist to this song. McCartney was primarily inspired by a girl named Melanie Coe, whom he read about running away from home in a newspaper. It turns out the Beatles actually met her! Three years earlier, Coe met the band while they went on a tv special. Coe later told people that the song got almost everything right. Talk about authenticity!

Side One concludes with another strange Lennon offering, Being For The Benefit of Mr. Kite!. While filming a promotional video for Strawberry Fields Forever in Sevenoaks, Kent, Lennon and Harrison went into an antique shop. There, Lennon found an old poster from 1843 promoting a circus act. Filled to the brim with antiquated Victorian language and fanciful advertising for Pablo Fanque’s fair, Lennon immediately bought the poster.

Later, when he was feeling a bit low creatively, Lennon copied more or less what was on the poster for the lyrics of his next song. Hardly original. However, when it came to creating the sound of the song, originality dominated the day. Lennon wanted to “smell the sawdust” from an old fairground, so Martin exhaustively played a variety of organs while sending engineer Geoff Emerick on a wild excavation to find old fairground recordings and calliope music to get the right feel for the song. Being For The Benefit of Mr. Kite! is one of the most complex recordings the Beatles ever made. Lennon initially hated the result, but shortly before his death he called it “pure”, presumably meaning he changed his mind.

After Side One’s musical theatre, drug trips, whimsical self-improvement, family dramas and a detour to Queen Victoria’s summer holiday, what could possibly open Side Two? Answer: George Harrison.

Within You Without You, recorded without any participation from Harrison’s bandmates, features every Indian instrument under the sun. From sitars to tamburas to tablas all played by a variety of specialist musicians, Harrison’s burgeoning interest in Indian music and Hinduism could no longer be contained. The song’s philosophical lyrics, sung by Harrison in a curious drone voice, only added to the mystical feeling of the track. Harrison, mildly fed up with the whole Beatle thing by that point and not totally on board with McCartney’s alter-ego band idea, ironically helped Pepper’s thematic concept with this Beatles deep cut. The song runs for just over five minutes, making it the second-longest track on the record.

The song would prove divisive among critics, but not among Harrison’s bandmates, who showered it with acclaim. Even the hard-to-please Lennon was impressed. Within You Without You’s praise among the band and George Martin contrasts sharply with Harrison’s initial offering, Only A Northern Song. Written as a whinging and bitching exercise about his junior role within Northern Songs, the Beatles music publisher, the band and Martin hated Only A Northern Song with a vengeance. It wound up on the throwaway Yellow Submarine album. Harrison seemed a bit insecure about his superior Indian-flavoured tune, and so he requested that a laughter sound effect be tacked on to the end of the song.

Sgt Pepper continues with When I’m Sixty-Four, another McCartney composition. The song was actually one of the first McCartney ever wrote, and used to be played when the band was in residence in Hamburg, West Germany. When it was deemed fit for purpose and brought out for Sgt. Pepper, it was originally going to be the B-side to Strawberry Fields Forever before finally being shoved onto the album.

The sound of McCartney pretending to be sixteen and wanting to be sixty-four with his girlfriend created an endearing quality that’s only enhanced by the musical feel McCartney wanted—1920s music hall. Complete with a clarinet and woodwind section scored by Martin, When I’m Sixty-Four is pure vintage. Lennon was ambivalent about the track, but the band gave it their all regardless. I bet that if someone threw the song into a vaudeville playlist for a gag, only real Beatles fans would notice. It certainly adds to the illusion that Pepper is a mishmash performance of diverse musical acts.

Lovely Rita comes next, an act of pure and banal fiction complete with a jaunty piano solo played by Martin. McCartney found the American name for traffic wardens, meter maids, both inspiring and delightfully alliterative. So he cooked up this ditty about a guy who falls in love with a meter maid, takes her out, gets back to her place aaaaannnddd…sits on the sofa with her sister. What a bummer, dude. Recording the track was a fun affair, both for the Beatles and the band next door. Locked away in the adjacent studio, Pink Floyd was recording their equally psychedelic debut album. Pink Floyd met the Beatles later in the session, no doubt interrupting their silly recording antics. Scattered throughout the track is a harmonium-like sound. It wasn’t an instrument but the band blowing on a strip of the cheap, godawful linoleum toilet paper EMI so generously provided for their studios. Lennon and Harrison added to the naughtiness by making series of high-pitched moans and groans before calling out “leave it” to conclude the track.

In later years, a real traffic warden claimed she was the inspiration for the song. McCartney denied it and Lennon concurred saying, "he [McCartney] makes ‘em up like a novelist.”

The final leg of Pepper begins with a Lennon tune, Good Morning Good Morning. Long hated by its creator, it’s hard to see what caused Lennon’s ire. The sound of a cock waking up the farm is swiftly followed by a roaring brass band, backed by Starr’s punchiest snare sound on any Beatles recording. Lennon’s lyrics reflects the sense of creative stagnation he felt living in suburban Weybridge. The song’s title came from a cereal commercial jingle, and the lyrics referenced a soap opera he was into called Meet the Wife. On top of all this frustrated music, McCartney, rather than Harrison, adds a stinging guitar solo while Lennon commandeers the sound effects library to create a unique finale.

Starting with a chicken, a sequence of animal noises plays over the rhythm section, each “devouring the one that came before it”. So a cat is eaten by a dog, the dog by more dogs, and so on. What turns the idea from barely creative to jaw-droppingly original is how the last animal sound, another chicken, is synced up to segue into the next track.

The reprise of the title track begins with a guitar mimicking the sound of a chicken being strangled. Then Starr’s impatient kick drum and an off-the-cuff Lennon remark lead McCartney counting into one minute and eighteen seconds of blitzkrieg rock ‘n roll. Sgt. Pepper’s band is making their final bow. The sound effects of the crowd further add the illusion of the album being a live show. The brevity of the track is what makes it good, especially considering how nicely the track segues into the best album finale in history.

A Day In The Life is the pinnacle of the Lennon-McCartney songwriting partnership. Lennon’s soft acoustic guitar, accented with maracas played by Harrison, strums away carelessly while McCartney’s piano and thumping bass line join in over Lennon’s lyrics.

His everyman lyrics are concerned with he saw in the newspaper. “I read the news today/oh boy.” A bored observer of the world, mildly intrigued by what he sees, is soon joined by Starr’s toms. The tom drums hit with the force of a timpani in a grand concert hall. Then the song takes its famous twist with the line “I want to turn you on.” Lennon’s proclamation is followed by the voice of roadie Mal Evans counting out the bars while a giant orchestra swells up into a soundgasm of tremendous force before abruptly segueing into a middle-eight sung by McCartney over a cheery piano part. McCartney’s jaunty verse contrasts sharply, and wondrously, with Lennon’s barely concealed lethargy. McCartney’s character concludes his morning when he “went upstairs and had a smoke/and somebody spoke and I went into a dream.” Lennon’s harmonising voice takes us through air before we land back on the final newspaper verse. This time, 4000 holes in the roads of Blackburn, Lancashire, warrant our attention before the orgasming orchestra returns. Then, at the highest point—of the orchestra swell, the song, the album, maybe even the Beatles’ entire career—a triple piano chord strikes with the force of Jupiter’s thunderbolt.

And then, that’s it. The 50+ seconds of echo stemming from the three piano chords being played simultaneously hangs in the air to conclude the album…sort of. At the end the piano echo, a brief high-pitched whistling, audible to the dogs listening to the album with their owners, is followed by a gibberish track of nonsense jammed into the run-out groove. For those without an automatically retracting stylus, the sound of the Beatles losing their minds would go on forever and ever.

Conclusion.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band really does live up to the hype. A work of art conducted by talented artists all cooperating with each other is truly a force to be reckoned with. Like most incredibly successful works, it led to the artist’s undoing. The Beatles never truly delivered a united album after Pepper, though the post-Pepper albums still crush it in terms of genius. Pepper’s carefully chosen crossfades gave it the feeling of being a complete whole, a novel rather a collection of short stories. Albums weren’t really like that prior to Pepper and most subsequent albums aren’t either.

Whatever the combination the Beatles employed, there is a good reason Pepper stands as a masterpiece of writing and music, now, forever, and always. It has a focus lacking in most novels, a brevity not found in most movies or TV shows, and a musical sophistication not found in most music.

This is how art is supposed to be done, and that explains why this rock band from Liverpool made its way onto the cover of Tony Judt’s history book. Plenty happened in Europe in the seventy-five years since the end of World War II, but Sgt. Pepper reminds us why the Beatles have a seat at the table with De Gaulle, the Iron Curtain, and the end of Communism.

They affected as many if not more lives.